Yellow-footed tortoise

(Chelonoidis denticulatus)

Individuals

A sample size of 30 motelos were available for study during the sample period. The group consisted of 15 males and 15 females and ranged in size from 4125 g to 11250g indicating a wide range of age classes.

Housing and care

These individuals were placed in a 300 m2 enclosure featuring natural vegetation for the behavioral observation period.

Release site

The rainforest conservation area of Selva viva is located on the shores of Rio Arajuno in Eastern Ecuador. To put it more precisely, it is found near the town of Ahuano, Canton Tena, Napo province. The forest of Selva Viva reaches from the mouth of Rio Cosanos down to Rio Napo. The protected area is continuously expanding and is at 1700 ha in 2014. The Liana Lodge, Runa Wasi and AmaZOOnico are located on the border of the forest on the shores of Rio Arajuno.

The forest is widely known for its abundance of wildlife. Within the limits of the conservation area, logging and hunting are strictly prohibited, whereas harvesting fruits, nuts and plants for medical use is permitted. The indigenous community of Ahuano adheres to these principles. Nevertheless, since the forest’s rich flora and fauna attracts loggers and hunters from elsewhere, the ban on logging and hunting can only be enforced grace to the official status as a conservation area. This is why this forest provides a safe haven for the animals of the wildlife rehabilitation centre AmaZOOnico.

Pre-release adaptations

Rapid personality tests were performed on each individual following the procedure of Le Balle et al. (2021). For this procedure, one tortoise at a time was moved to a 2 x 2 m pen adjacent to the main research enclosure. Within this

pen, four measures comprising the personality test were taken: 1) stress untuck (whether the motelo untucked its head from its shell within 10 seconds of being tapped on the noise with a pen), 2) stress latency (the time in seconds until the motelo took its first step after the nose tap), 3) exploration (the count of distinct exploratory behaviors exhibited by the motelo in a five minute period following its first step), and 4) novel object (the time in seconds it took for each motelo to inspect a yellow plastic ball placed in the pen following the exploratory period, up to a maximum of five minutes). These measures were combined to create a

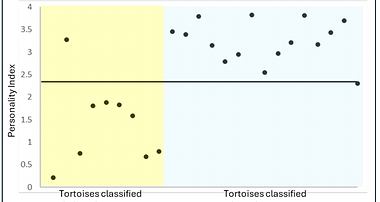

personality index for each motelo. The index ranged from 0 to 4 with 0 indicating a less active personality and 4 indicating high activity.

The extended behavioral tests were performed between April and November 2024. During an observation session a single motelo was observed for a one-hour period and its behaviors (classified by a standardized ethogram) were recorded continuously. On each given observation day, the specific motelo and hourly interval (between 7:00 and 15:00) of observation were chosen at random. The same motelo was never observed at the same hourly interval twice to reduce any effects of time of day on behavior.

Motelos were classified into distinct behavioral types using the Ward Hierarchical Clustering method in R v4.1.1. The analysis was based on the frequency of time spent in each of five behavioral classifications: 1) active non-social, 2) human affiliative, 3) non-active, 4) social aggressive, and 5)

social passive. Groups were considered to be significant at a 95% confidence level. For post-release monitoring, six individuals were chosen to be fitted with Iridium GPS tags supplied by Advanced Telemetry Systems. One representative from each of the five classified behavioral types was chosen at random to be tagged, with the sixth individual chosen from the largest behavioral group. Accordingly, all behavior types would be represented in post-release monitoring. The tags were programmed to record tortoise location at six evenly spaced intervals throughout the day (3:00, 7:00, 11:00, 15:00, 19:00, and 23:00). GPS tags were fitted using a watertight epoxy, and all motelos received a thorough veterinary examination before release.

A total of 1372 distinct behavioral observations were made of the 30 motelos across 101 hours of observation. Four hours of observation (each hour on a separate day) was targeted as the minimum observation time for each individual. However, in August the research enclosure received damage to its foundation and eight motelos escaped and were not recovered. Of these individuals, three were previously observed for two hours and five for just one hour. The remaining 22 individuals were all observed for a minimum of four hours with two individuals being observed for five hours. All 30 motelos took part in the rapid personality test. The average personality index value was 2.38 with a minimum of 0.22 (motelo #4) and a maximum of 3.82 (motelo #12).

The cluster analysis revealed five significantly distinct behavioral groups accounting for 24 motelos. The remaining six motelos could not be assigned statistically to any behavioral group. A post-hoc analysis of behavioral histograms suggested the following classifications for the behavioral groups: Group 1 – inactive moderately social, Group 2 – inactive asocial, Group 3 – highly inactive, Group 4 – highly exploratory socially passive, and Group 5 – highly active socially aggressive. The highly exploratory socially passive group was the largest with ten individuals and consisted mainly of large females. The highly active socially aggressive group was notable as it consisted entirely of males and mostly of a small size, indicating that this behavior type is strongly linked to age and gender. Personality indices correlated very strongly with behavioral group classification. Motelos belonging to inactive behavioral groups (N = 9) had an average personality index of 1.42 with only one individual in this group exhibiting a personality index higher than the average of the entire population (motelo #5, personality index = 3.27). This motelo was one of the escaped individuals that was only observed for one hour, and thus, its behavioral group classification has less confidence. Motelos classified in the active behavioral groups (N = 15) had an average personality index of 3.23, with all individuals except one (tortoise #30, personality index = 2.31) above the population average. One motelo from each behavioral group was chosen at random to be released with a GPS tag, selection included an equal number of males and females. GPS tags were affixed to the motelos’ carapaces on January 28, 2025, and the individuals were moved to a smaller enclosure where GPS adhesion could be monitored, and functionality of the units could be tested. The motelos were then brought to a location in Selva Viva Protected Forest (~3 km from amaZOOnico) and released on February 4, 2025.

Discussion and future steps

The observational portion of the project confirmed the findings of recent studies that motelos do have distinct personalities that can be measured and classified. An important advance is our finding that simple personality tests may be adequate for classifying motelo behavioral types without extended behavioral observations. In our case, personality tests averaged just 30 minutes and largely suggested the same behavioral classifications as four to five hours of extended observation. This is important as resource limited rescue centers often cannot dedicate such large amounts of time to intensive behavioral observations, particularly when managing large populations of individuals. Whether motelo behavioral types correlate with differential outcomes of release success will be determined by post- release GPS monitoring. Whatever outcome is shown by post-release monitoring, caution should be used when interpreting results as a population size of six individuals will not be sufficient for statistically significant results. The results, however, will serve as an early indicator of the link between personality and release outcome, and it is our hope that the efforts will inspire similar studies with tortoises and other species groups. Virtually no scientific literature exists on post-release monitoring of any wildlife groups that have been rehabilitated and released following rescue from illegal captivity. Until recent advances in GPS technology, managers have released rescued animals with little knowledge of survival outcomes and accordingly little understanding of how to adjust rehabilitation programs to enhance success. By correlating behavior types with release success in motelos we are taking the first step towards enhancing rehabilitation programs for this and other species and ultimately enhancing the health of forests that will benefit from restored wildlife populations.